Search for cellular causal link between coronavirus and hearing damage heads to the morgue

Covid

Attempts to link the novel coronavirus to hearing problems has so far led to patchy data. But an ear surgeon leading a research team at Johns Hopkins University may be cutting his way through cadavers towards plausible cellular mechanisms.

Possible explanations as to how the coronavirus could lead to severe hearing problems have been investigated in different countries, but the search for an exact causal link has been frustrated by some blanks drawn in academic investigations, and by practical considerations, such as the problem of how to make slides from fine enough bone sectioning in histological studies.

A diamond-made saw and a few cadavers

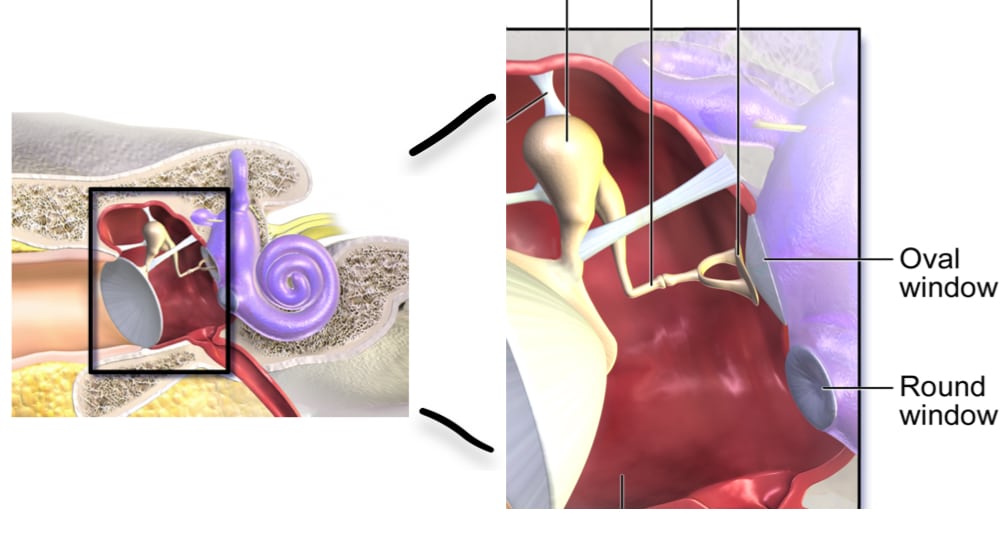

The latter problem is one that has been cleverly surmounted by researcher Matt Stewart, working at the USA's Johns Hopkins centre. Following up on Tokyo research that found ACE 2 receptors and related proteins—in the Eustachian tube, middle ear spaces, and cochlea of mice, Stewart wanted to use human cadavers to see if these same key receptors, already shown to be the point at which coronavirus enters cells, can be found in their inner ear structures.

But unlike those of mice, human bones need a year before they are soft enough to slice to the fine dimensions required for such microscopic analysis of inner ear parts. Stewart's memory came to the rescure, as he recalled his graduate student experiences in geochemistry, when he had used a diamond mineralogic saw with a blade just .03 inches in thickness.

The National Institutes for Health would not pay the $7k price of the saw, but Stewart found private funding and the research progressed. Results from six cadavers that did not have a Covid-19 infection show vulnerable cell receptor types in the middle ear, cochlea, and balance system, meaning the novel coronavirus could potentially cause hearing damage by directly invading cells.

Early results promising

Stewart presented the results at the American Neurotology Society’s meeting in September 2021, and his team is preparing a manuscript to submit to a journal, so the study has not yet been peer-reviewed. The research seems to be on the right track to merge on the road to knowledge with complementary studies, such as one in the Boston area, led by Stanford University surgeon Konstantina Stankovic, looking at vulnerability to viruses. These involved tissue studies that confirmed that patients’ inner ears contained the same proteins that Stewart found in his cadaver research.

Stewart’s team is now planning to look for evidence of direct invasion in the cells of hearing and balance system organs using samples from Covid-19-positive cadavers.

Source: Undark/Medscape