Gene-editing fix for progressive hearing loss comes closer

genetics

Progressive hearing loss is just one of around 5,000 diseases linked to single-gene changes, but geneticists have so far lacked the precision tools to stop us developing these conditions. A genetic cure for this kind of deafness just came a huge step closer.

US Researchers from Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital have announced a breakthrough that brings us closer to times in which inherited forms of deafness could be prevented through a gene editing process that uses enzymes known as "molecular scissors". The journal Nature Medicine announced this July that the process has been successfully used not only on so-called "Beethoven Mice"—whose progressive hearing loss mimics that suffered by the great composer—but also on lab-grown human "Beethoven" cells.

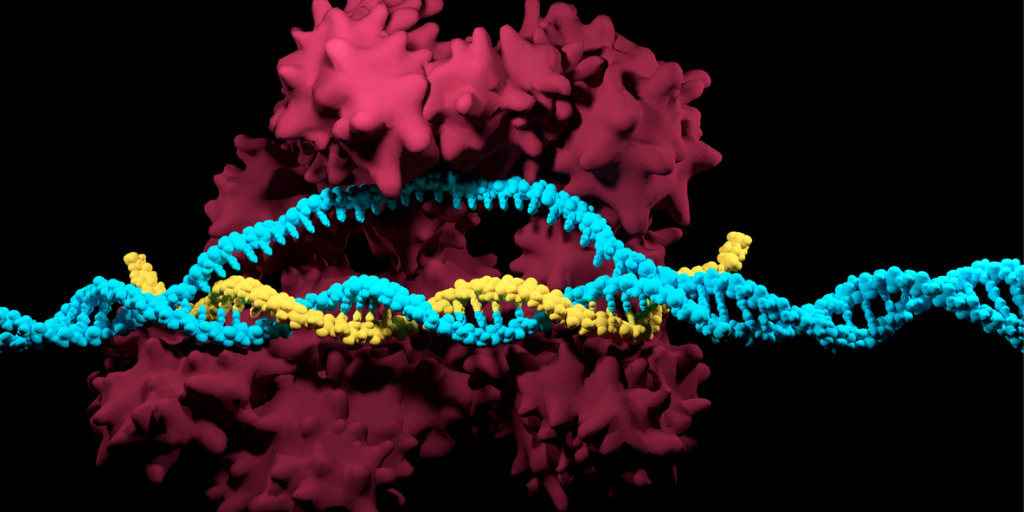

We receive genes as pairs, one from each parent. If one of these copies is defective, it can lead to conditions such as progressive hearing loss (after six months in the lab mice, but affecting humans from about the age of 20). This so-called CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing process enabled the researchers to identify and "snip" out the deafness-causing mutated gene, sparing the healthy copy, a major breakthrough.

The findings show that the approach effectively switched off the defective copy and avoided hearing loss in animals typified by the development of the condition. In mice, the therapy was administered shortly after birth. After a month, untreated "Beethoven" mice could hear low-frequency sounds but had notable hearing loss at high frequencies. By month six, they had lost all their hearing. But the treated mice retained near-normal hearing at low frequencies, some of them even at high frequencies.

The level of precision achieved by these "molecular scissors" is key to this research advance: the system has to spot a single incorrect DNA letter among three billion in the mouse genome.

There is still a long way to go before these results translate into an accurate therapy, but the gene-editing part has infused great hope into the search for a genetic solution, since the same approach could be used for other inherited diseases originating in a single defective copy of a gene.

Source: The London Economic