"BAEPs must always be seen as a support resource for behavioural audiometry tests”

Electrophysiology

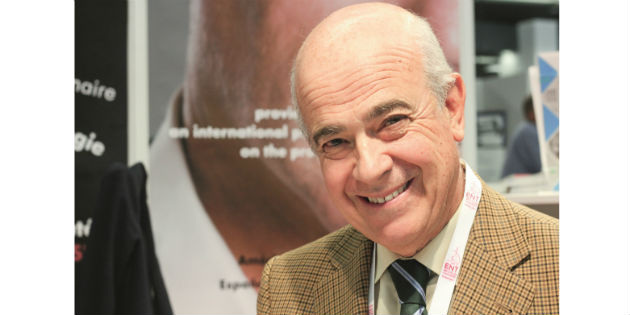

Interview to Spaniard Dr. José Juan Barajas, recipient of the International Award in Hearing American bestowed by the Academy of Audiology and founding father of the Canary Islands clinic that carries his name.

The award is given inrecognition of his contribution over many years to enabling students from different countries to work inelectrophysiological practices in diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation of voice, language, and hearingdisorders, as well as for other oustanding points of merit during his extensive career.

What does this award mean to you, and whataspects of your career does the American Academy ofAudiology (AAA) wish to highlight by bestowing it on you?

I guess it’s for the whole of my career, for myprofessional dedication in relation to American audiology, whichstands as a model for what we do not have in Europe, a highlyclinical model. I have had plenty of contact with my colleaguesthere, and I believe that this acknowledgement has come becauseI have reproduced the American model of audiology. And to thedegree to which I have expressed my gratitude to them for helpingme to know who I am. It is cause for special gratitude, since one often feels an outsider; otorhinolaryngologists consider me anaudiologist, and audiologists think of me as an otorhinolaryngologist.I see myself as an otorhinolaryngologist who has nurturedgreat enthusiasm and devotion towards audiology.

What has been your contribution to the InternationalSociety of Audiology as a researcher. How long have youworked with this organisation, of which you were presidentfrom 2010 to 2012?

My research work has been centred on the electrophysiologyof the central nervous system, my studies covering from the end organ to the cortex. I am basically an electrophysiologistof the central nervous system. I have tried to be of use to internationalaudiology from positions of top responsibility on theexecutive committees of different societies. I was president ofthe International Society of Audiology (ISA) and the InternationalAssociation of Physicians in Audiology (IAPA). In my case, thesetasks on international committees have been an honour as wellas a motive for personal engagement and commitment. Theseexecutive activities have helped me improve my knowledge ofthe human condition. My conclusion is that there are no nationalcharacters, that integrity is the product of individual values, andthese can blossom anywhere in the world.

Since you mention this international perspective, inthe US for example, how would you define the situation inSpain?

It has improved substantially in recent years and thereare now people there with medical training who have a specialinterest in audiology. The Spanish Society of Audiology (AEDA)works well, and its president, Franz Zenker, is one of my disciples.He has a wide vision of the discipline and knows how tointeract with professionals of different backgrounds. Each year,AEDA organises very interesting and instructive conferences. Inpast times, audiology was looked on by otorhinolaryngologistsas a minor field, so much so that anyone in my service whobehaved badly was sent to carry out audiometry tests, ensuring(he laughs) they wouldn’t get to the operating theatre. I’d like topoint out in this respect that I am profoundly grateful to thosewho helped train me. Fernando Olaizola was not only a brilliantsurgeon but he also inculcated in us an academic yearning aswell as stimulating us to use our critical spirit. Under his directionat Madrid’s Clínica del Trabajo, we organised the first coursesin Spain on impedance testing, which had a big impact on thedevelopment of audiology in our country. For some time, I formedpart of the SEORL audiology council. In 1983, I was co-authorof the Spanish Society of Otorhinolaryngology presentation onevoked auditory potentials.

To what extent in the future will brainstem auditoryevoked potentials (BAEPs) be used in audiology practices?What will the right degree of implantation be?

They must always be seen as a support resource for behaviouralaudiometry tests. First, you must look at how a child reactsto sound. This concept is crucial, and independently of all typesof potentials that may be used. I receive many evoked potentialswith indications that are debatable. The audiologist’s primary useof evoked potentials is to identify responses up to intensities thatcan be correlated with psychoacoustic thresholds. It is easy toimagine that the main candidates for electrophysiological studiesare those subjects who cannot cooperate in conventionalpsychoacoustic studies either for reasons of age (newborn andchildren in the first year of life) or due to congenital defects ofsome kind. In both cases we need not only for brain responses to be obligatory but also to make sure results are not affectedby sleep or sedation. In any case, before sending a child or adultfor a prosthetic fitting or a cochlear implant, one must haveas clear an idea as possible of the behavioural responses. Onthis point it is important to corroborate that, before a definitivediagnosis is established, the different tests of varying validityand reliability that have been carried out are interpreted as awhole (cross-checking).

On the subject of tests that produce an “automaticresponse”, on what groups of people would it be useful tocarry these out?

Evidently, with a newborn child we are alwaysgoing to have to use a battery of tests that do notrely on the cooperation of the subject. It is desirableto avoid things that can contaminate theresponse (noise and movements). Each techniquehas its advantages and limitations, and it is ourresponsibility as therapists and/or researchers toknow in each case what we want to obtain with ourexplorations. It is not about putting electrodes onthe head of a child or adult; the important thing isto know how to design a sequential mental plan ofwhat we wish to achieve in order to establish theaudiological, neurological, or maturation status ofany particular subject.

What other electrophysiological testsdo you see as recommendable for everydaypractice in hearing aid fitting?

BAEPs, in both click and toneburst forms, andSSEPs (steady state evoked potentials). Both BAEPand SSEP can be used in sleep and/or sedation andare complementary due to their different dynamic range. BAEPpotentials are the more robust and reliable in auditory evokedresponses, and they are unique in determining type of hearingloss. Despite the time that has passed since their introductionin clinics, BAEP potentials constitute the “golden rule” amongauditory evoked responses.

BAEPs present a dynamic range of 80-85 dB, so they do not allowfor establishing thresholds in profound hearing loss. SSEPscover a dynamic range of 110-120 dB, so are more appropriatefor indicating any mode of training/rehabilitation in subjectswith profound hypoacusis. Cortical potentials, despite needingpatients to be awake, are also interesting clinically. The presenceof these components indicate in some way that the stimulushas unleashed a response that has reached the cortex via theauditory pathways.

What research project are you currently working on orhave in view?

In correlation of sonority established through psychoacoustictests with responses obtained through SSEPs. It is a question of setting up a series of criteria to see if we can infer sonoritythrough these SSEPs that we would be able to obtain throughpsychoacoustic testing. The ultimate aim is to find out whetherthe amplitudes and intensities of the response of the steadystate evoked potentials can be instrumentalised for hearingprosthesis fitting.

You talked, did you not, on this in your presentation atthe last world otorhinolaryngology congress, IFOS 2017?You mentioned the concept of “loudness”…

Loudness is an intimate and non-transferable sensoryexperience. Psychoacoustic tests for loudness do not allow usto establish the sensation of loudness growth, which is preciselywhat we try to infer based on SSEP electrophysiological results.

Does this mean that the psychoacoustic tests could bedispensed with?

Only in population groups where we cannot obtain sonoritythrough a psychoacoustic form. In subjects with normal hearingone can correlate sonority quite closely with electrophysiologicalresults, but it is still to be determined whether that correlationholds up in subjects with hypoacusis.

What institution is supporting this line of research?

The Clínica Barajas and the Fundación Canaria Dr. Barajasfor the prevention of deafness.

From your renowned wealth of publications—66articles and 157 presentations, according to the AmericanAcademy—which would you highlight? Could you pleasemention a particular contribution you are especially proudof?

Without doubt, having been able to build a team in asmall medium and in very precarious conditions. Being able tobring enthusiasm to the projects and research inquiries we havepresented in top international forums. I would not value so muchjust one specific contribution, but having been able to inculcateenthusiasm for science in some younger colleagues. And havingbeen able to share unforgettable moments of academic debate.

And, besides everything, on an island…?

A small island, in a small private space…It has beenmiraculous, and this is down largely to my having brilliant andenthusiastic people around me.

What functions do the Clínica Barajas and theFundación Doctor Barajas fulfil, respectively? How do theycomplement each other?

Treatment, teaching, and research activities. Naturally, somemoments have brought greater productivity than others. My main legacy is not a tangible. Life is much more interesting when we havea question to answer. I believe it is worth creating an atmospherein which those around one are shown how enriching it is to havethe possiblity to do research.

Are you, perhaps, thinking about the research situation inSpain, because it will be highly different to the US?

There is a great difference between Spain and a countrylike the US. Comparing the scientific production of Spain withthat of the US is to lose one’s sense of proportion. In the US, theresources devoted to research are immense, and above all themost important thing is American society’s great tradition ofscientific activity. In the US, two conditions are behind sciencebeing especially prosperous: 1) respect for merit; 2) the balanceof power at work in general in American life, and in scientific lifein particular. Spanish science has come on substantially, however.In Spain, papers are being produced with increasing rigour, thereis better education in languages, and international literature isbetter known than before.

How, from your perspective, has technological progressinfluenced the production of cochlear implants and hearingaids in recent years? What challenges and unfinishedbusiness await us?

Throughout my career there have been discoveries thathave changed the essence of professional practice. Thesefrontline innovations embrace not only the diagnostic area butalso treatment. My career began just when brainstem potentialswere being introduced to clinics, and impedance testing wasbringing a new vision of how to approach study of hearing sensitivity.Otoacoustic emissions proved fundamental in helping toachieve universal neonatal screening. Cochlear implants, imagingtechniques, and so on. In my field, I have had the chance to getto know the main movers of these changes relatively well. WhenI think about those people and the proximity I have had to them,I feel especially fortunate.

What challenges are left from a technologicalperspective?

I rather believe that these are going to come from the geneticand molecular side. The future will have to be based much moreon biological investigation of the end organ, in order to treatdisorders without any invasive activity. Everything we are currentlydoing does not solve the intimate problems of the mechanismsthat produce the dysfunction. Why do cells age and how can weavoid it? Today we put cables into the ear and we help the patientto have better communication. In the future, why would we notlook at things in quite another way?

Source: Audio Infos América Latina