Buñuel's "bloody deafness"

cinema

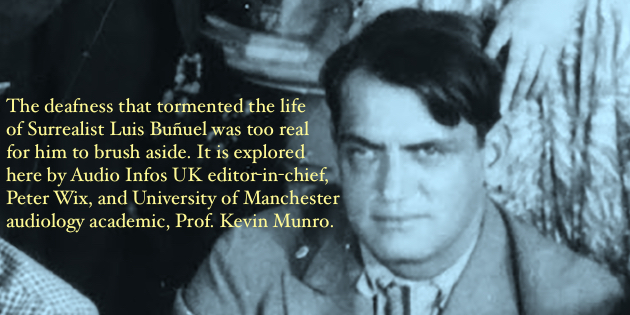

Deafness brought filmmaker Luis Buñuel despair and isolation. Barely tackled in his acclaimed autobiography, the Surrealist's hearing loss is more deeply referenced in a fine new collection of his private correspondence recently published by Bloomsbury: Luis Buñuel - A Life in Letters.

The Spanish-born surrealist Luis Buñuel (1900-1983) directed no fewer than seven of the titles in Sight & Sound’s 2012 critics’ poll of the top 250 films of all time. He was a cinema giant who crossed the line between arthouse and mainstream. But perhaps the cruelest irony of a life dedicated to making us us challenge what our senses tell us, was the loss of Buñuel's own hearing sense, a blow that soured the second half of his life.

“One of the greatest tragedies in my life is my deafness, for it’s been over twenty years now since I’ve been able to hear notes. When I listen to music, it’s as if the letters in a text were changing places with one another, rendering the words unintelligible and muddying the lines,” he lamented in My Last Breath, his autobiography (ghostwritten,in fact, by his long-time friend and scriptwriter, Jean-Claude Carriere).

Long before his old age, Buñuel began to loathe public places with either music or muzak, preferring to cloister himself in the silent bars of hotels. Yet in his youth he had played violin and banjo, and despite the iconoclastic beliefs that led him and fellow surrealists—such as his early collaborator Salvador Dalí…to attack the bourgeois establishment, the young Buñuel was a lover of music from the Western classical repertoire. Beethoven, Debussy, Franck, Schumann, and Wagner were his favourites.

“I’d consider my old age redeemed if my hearing were to come back, for music would be the gentlest opiate, calming my fears as I move toward death.” *

Along with the music he lost were many favourite sounds, as well as social and work-related events that became torturous for him.

No sound is lovelier than that of the rain. There are times when I can hear it, if I wear my hearing aid, but it’s not quite the same, of course.*

Though Buñuel’s deafness had affected him for some 20 years when he wrote, in 1963, from Mexico City, to Guillermo de Torre (dadaist and essayist, brother-in-law of Jorge Luis Borges), it was clear how tired he was with the struggle to hear:

I never answer the telephone, and when I did that time, the thing I always fear will happen happened. I can’t hear names and whoever is calling thinks I’ll get them if they shout loud enough. A hopeless task. All that happens is that I get anxious, unable to associate ideas, almost obnubilated. To me your name sounded like Yerma de Sorra (I turn the ‘t’s into ‘s’s and vice versa).**

October 24, 1966

I’m going to leave it a few days, because I spend Sundays alone in my room to give my terrible hearing a rest from the daily racket. The mental battle involved in mingling with crowds led to Buñuel cancelling even such important outings as collecting awards, as on August 29, 1969 when he informed the director of the Venice Film Festival, Ernesto Laura: I have been suffering for two days now from an unpleasant nervous tension that has had a particularly bad effect on my hearing. For the moment I have lost almost all auditory function. The doctor says a few days of treatment should begin to correct this, relatively-speaking, that is, as I’ve had trouble with my hearing for some time now: under these conditions it would be unwise of me to take on the meetings, conversations, interviews, etc., to which you have so kindly invited me. So, it is with sincere and deep regret that I find myself having to cancel my trip to Venice.

Frustration and Isolation

One letter from the new Bloomsbury publication shows just how early Buñuel was affected by hearing loss, but at that time he was still able to be frivolous about it.

To Gustavo Pittaluga (composer of many of Buñuel’s soundtracks)

Ollibood [Hollywood] February 15, 1945

Forgive me for saying how healthy and handsome I am at the moment. The only thing holding me back now is my deafness, which, if it carries on, will soon have me composing a patétique or painting a series of caprichos.

By 1964, in a letter from Mexico City to the French film producer, Pierre Braunberger, Buñuel admitted to being ˝a slave to my deafness˝. Five years later, to his friend and scriptwriter, Jean-Claude Carriere, his lines captured the isolation his deafness had caused:

Thanks to my deafness, I have my lunch apart from the others, supper alone, then bed at 8:30.

By 1972, in a letter to to the Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes, no longer attempting to mask the despair it caused him, the filmmaker moaned:

I am at your service, although my cloistered life precludes certain excesses. I get up at 06:30 and go to bed by 9pm at the latest. I have to see so many people and the nervous tension at the end of the day is most unpleasant. Bloody deafness.

And just five years from the end of his life, his humour on the subject had become as dry as his favourite tipple:

To Eduardo Ducay, Mexico City, April 17, 1978

As well as being deaf, I shall soon be using two pairs of glasses like Goya. It makes me quite isolated and my only comfort is the dry martini that transports me momentarily back to my youth.

Martini or not (and the director took just one, religiously, every afternoon, to fire his imagination) the hardship Buñuel experienced through having lost his hearing is very clear in his letters.

Hearing healthcare professionals and experts know better than most just how disorientating and tiring this loss is for those who must endure it. Prof. Kevin Munro, Director (Research) of the Manchester Centre for Audiology and Deafness (ManCAD) agrees that avoiding gala evenings and people speaking a variety of languages, as well as eating meals apart, are normal and understandable responses from hearing loss patients to highly challenging and stressful situations. Given Buñuel’s testimony on the discomfort he experienced, the assertion in the introduction of the new collection of correspondence that Buñuel ˝would use his well-known hearing problems to excuse himself from public appearances˝ might ignore the severity of the impact of hearing loss on those who suffer it. In other words, even if the filmmaker sometimes used his deafness to excuse himself from events he found tiresome, his hearing difficulties would have made even otherwise appetising invitations difficult to endure. Although, at the beginning of his conversations with the novelist Max Aub, he confessed ˝you don’t need to raise your voice; I hear well with my hearing aid˝, the reality of Bunuel’s situation is repeatedly reinforced in the book’s letters. Hearing loss is discouraging.

In My Last Breath, the aged director ruminated: ˝Even today, I sometimes wonder if it’s true that blind people are happier than the deaf. I tend to think not, yet I once knew an extraordinary blind man named Las Heras who’d lost his vision when he was eighteen and had tried many times to commit suicide.˝

The surrealist imagination, and a possible cause of his loss?

As with all surrealists, Buñuel’s work focused sharply on sense data, and fulfilled the mission initiated by 19th-century poet Arthur Rimbaud: the ˝derangement of the senses˝.

In his 1970 film Tristana, the spectator is drawn into scenes featuring deaf characters through the use of exaggerated bell chiming or gushing water, all symbolic reminders of the distorted sounds Buñuel himself experienced. His films often supersized sounds or played around with speech, as they famously did with visual information.

Images from his childhood in Aragon stayed strong in Buñuel’s imagination throughout his life, though many surfaced in his early work. In a bubbling 1929 letter to his student friend from the famous Generation of 27, José Bello, he mentions the title of the book he intends to publish—The Andalusian Dog—˝which made Dalí and me piss ourselves laughing when we came up with it˝, sending Bello his poem, The Rainbow and the Poultice, which contains the lines:

In a few minutes two salivas

will come down the street leading

a school of deaf-dumb children by the hand.

Would it be rude of me to vomit a piano on them

from my balcony?

In Buñuel and Dali’s cinema masterpiece of that year, also called Un Chien Andalou, that piano from his poem had become two pianos containing dead, decomposing donkeys. A year later, in The Golden Age, the protagonist’s fit of jealousy is accompanied by a soundtrack of ritual Easter drumming from Buñuel’s home village, Calanda. He used the drums several times in his films.

˝Nowhere are they beaten with such mysterious power as in Calanda, without pause from noon on Good Friday until noon on Saturday. Up until recently, I often beat the drums myself,˝ he confessed in his autobiography. ˝As the bell tolls the noon hour, the drums suddenly fall silent, but even after the normal rhythms of daily life have been re-established, some villagers still speak in an oddly halting manner, an involuntary echo of the beating drums.˝

The 24-hour drumming of Calanda has been measured at 120 decibels. Buñuel was exposed to this throughout his young life and periodically, he says, in later life. Could his beloved drums of Calanda have caused damage leading to his hearing loss?

It depends on susceptibility, says Audiology academic Prof. Kevin Munro: ˝Excessive exposure to loud sound can damage hearing. Drums can certainly be loud. The question is whether the duration of exposure so excessive that it resulted in damage? Individual susceptibility varies so a proportion of the population (for genetic or/and environmental factors) may be more susceptible and end up with damaged hearing,˝ Munro points out.

*My Last Breath

**Luis Buñuel – A Life in Letters

Sign in

Sign in