Mass Eye and Ear study revives theory that tinnitus could have its origins in cochlear neural degeneration

The goal of silencing tinnitus will not advance until there is understanding of the mechanisms underlying its genesis. This is the firm belief of Dr. Stéphane F. Maison, principal investigator at Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, and clinical director of the Mass Eye and Ear Tinnitus Clinic.

To advance this understanding, Dr. Maison – also a member of Mass General Brigham – and colleagues have authored a recently published study in Scientific Reports that takes the tinnitus cause investigation back to where it lost ground, showing that tinnitus may be triggered by a loss of auditory nerve, including in people with normal hearing.

And the trail along this tinnitus-related investigative strand dovetails with work seeking a chemical cure to hearing loss itself.

Why was a neural degeneration tinnitus origin theory knocked back?

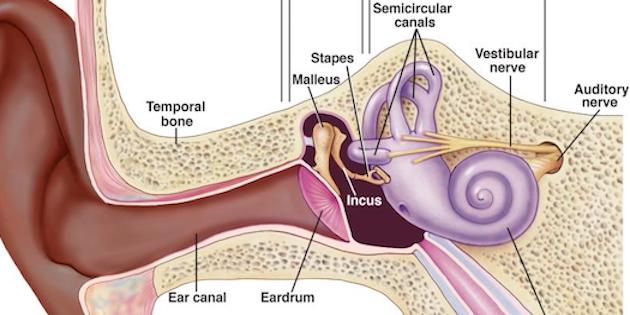

The buzzing, humming, ringing or roaring sounds that tinnitus sufferers experience have long been considered to arise as a result of a maladaptive plasticity of the brain. In other words, the brain tries to compensate for the loss of hearing by increasing its activity, resulting in the perception of a phantom sound, tinnitus. Until recently though, this idea was disputed as some tinnitus sufferers have normal hearing tests.

But the discovery of cochlear synaptopathy back in 2009 by Mass Eye and Ear investigators revived this hypothesis when it was shown that patients with a normal hearing test can have a significant loss to the auditory nerve. In this latest study, Maison and his team sought to determine if such hidden damage could be associated with the tinnitus symptoms experienced by a cohort of normal hearing participants. By measuring the response of their auditory nerve and brainstem, the researchers found that chronic tinnitus was not only associated with a loss of auditory nerve but that participants showed hyperactivity in the brainstem.

In the study, statistical analyses followed comprehensive testing using audiometric thresholds, auditory brainstem responses/electrocochleography, middle-ear muscle reflexes, and medial olivocochlear reflexes. Concluding, the authors say their study “clarifies the association between biomarkers of peripheral neural deficits with tinnitus and is consistent with the idea that cochlear neural degeneration may serve as a peripheral trigger for excess central gain.

Future research will see the investigators aim to capitalise on recent work geared toward the regeneration of auditory nerve via the use of drugs called neurotrophins, proteins that induce the survival, development, and function of neurons.

“The idea that, one day, researchers might be able to bring back the missing sound to the brain and, perhaps, reduce its hyperactivity in conjunction with retraining, definitely brings the hope of a cure closer to reality”, said Maison.

Source: EurekAlert Mass Eye and Ear